There was no rest for weary rate watchers after last week’s rout. This week turned out to be even more volatile.

UK in The Spotlight (Still)

UK issues are still having a big impact. Last week’s rate spike was most readily attributable to market panic over a budgetary decision in The UK. Panic remained on Monday and intensified on Tuesday.

Why should the US care? Global financial markets are interconnected in many ways. Even though something that happens in The UK will have more of an effect on UK markets, if the effect is big enough, it’s felt around the world.

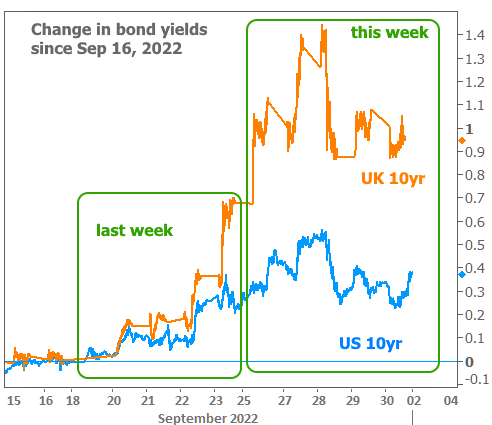

The drama of the past two weeks has been more than big enough. Additionally, UK and US bond markets (the markets that determine interest rates) are more correlated than most. Here’s an updated chart showing the relative movement of each country’s 10yr sovereign debt (higher yields = higher rates):

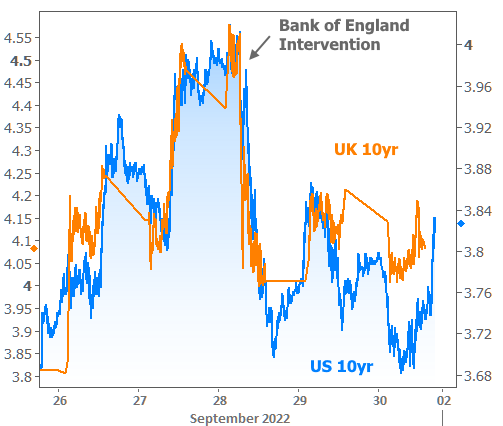

In other words, they took a sad song and made it worse. This was a very serious episode for global financial markets and especially for the UK. Markets expected some sort of official intervention on Tuesday, when it didn’t come, rates experienced their sharpest spike.

Then on Wednesday, the Bank of England (BOE) stepped in to sooth markets with an emergency bond buying announcement. While that didn’t undo all of the damage that had been done, it at least stemmed the tide of rising rates. Here’s a different visualization of US and UK 10yr bonds, this time with separate y-axes, simply to show the correlation in movement.

It’s not clear whether we’ve seen the last of fiscal policy fallout from the UK, but the BOE’s emergency announcement means that the next response won’t likely be as volatile.

It’s Not All About The UK

As dramatic of an episode as this may have been, it wasn’t all about the UK. Major central banks are generally enacting policies that push rates higher in the name of fighting inflation. The UK news wouldn’t have hit as hard if rates weren’t already up so much around the world and if markets weren’t already on edge about inflation and the associated policy responses.

The Fed is a frontrunner in rate-hiking policy. This refers not only to hiking the actual Fed Funds Rate, but also to decreasing the amount of bonds on the Fed balance sheet–something that puts additional upward pressure on longer term rates like mortgages. When that rate backdrop combined with the UK-induced volatility this week, it caused big issues for mortgage rates in the US.

All About Mortgage Rates

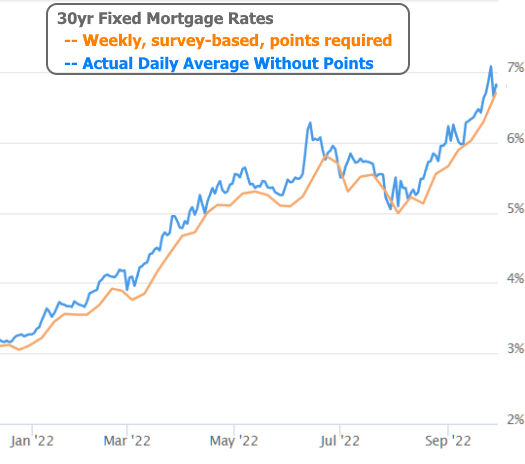

The average 30yr fixed rate topped 7% on Tuesday. Many lenders were still able to quote rates in the 6s, but that required “points” (a percentage of the loan balance paid upfront with the intent of securing a lower rate than would have otherwise been available). Adjusting for points, even the best priced lenders were over 7%.

But only a handful of ahead-of-the-curve lenders were actually able to offer viable rates over 7%. The ability to do this depended on the ultimate source of funds for the loans–the investor, to use industry terms. In the case of big banks and credit unions, the investor can be the bank itself. In other cases, the investor is the open market and in general, the open market has been quite averse to paying a premium for higher rates.

What is “Premium” When it Comes to Mortgage Rates?

Normally, a mortgage borrower can opt for a higher rate in exchange for lower upfront costs (or even a lender credit). This is referred to as “premium” pricing because investors typically pay a premium for a higher rate of return. That premium can then be used to cover upfront loan costs.

Premium pricing has been nonexistent at times in 2022, and the well ran almost completely dry over the past 2 weeks. There are a few reasons for the absence of premium. The simplest is that lenders don’t want to rely on earning higher interest over time to make their profits if risks are higher than borrowers will refinance at the first sign of lower rates.

The complicated reason is complex enough to avoid discussing in detail, but it has to do with the speed of the shift in financial markets and the fact that the mortgage-backed securities required to facilitate premium pricing simply don’t exist in the quantities required to create a healthy, liquid market. That absence of investor participation in realm of premium pricing means that lenders can actually offer you much better terms if you pay points.

Here’s the most striking example of the absence of premium pricing: for many lenders this week, they would make more money by giving you a loan at 6.625% versus 7.625%.

Wait, what?! Don’t lenders want to earn higher rates of return?!

They absolutely do, and indeed, some lenders with their own cash to lend are happy to offer the higher rate. Other lenders have to consider what investors are actually paying to acquire those higher rate loans, and in many cases this week, it was about the same for a 6.625% or 7.625%.

What’s Next For Rates?

On a mortgage-specific note, if market volatility decreases and rates manage to say sideways, premium pricing will gradually return. In fact, this was already happening in several noticeable ways by the end of the week.

As for rates in general, what’s next depends on inflation and the economy. The Fed is afraid of shifting to a less unfriendly stance too quickly due to lessons from the past. It has concluded that it would rather make the mistake of hurting the economy too much as opposed to the mistake of not doing enough to fight inflation.

As such, economic data is key. Strong data will only embolden the Fed’s position and put more upward pressure on rates. Sufficiently weak economic data, seen in multiple reports for a few successive months will get the Fed’s attention. In fact, this is their goal. They WANT to see the economic pain because they believe it will help inflation fall back in line with its target range. Assuming that pain translates to lower inflation, the Fed will pause to reconsider its policies, but this will take several months at a bare minimum, and if we take the Fed at their word, it would be more than year before they would consider cutting rates.

In the meantime, cues can come in bits and pieces–especially from the more important economic reports. The upcoming week has several of those with ISM PMIs on Monday and Wednesday. Then on Friday, we’ll get the next installment of the all-important jobs report–one of the only economic reports capable of challenging the Consumer Price Index (CPI) in terms of market movement potential. Incidentally, CPI is released the following week (Thursday, 10/14).

What’s Next For Housing?

In the meantime, the housing market is suffering. As long as that suffering is measured and not overly disruptive to the financial market, the Fed actually prefers it!

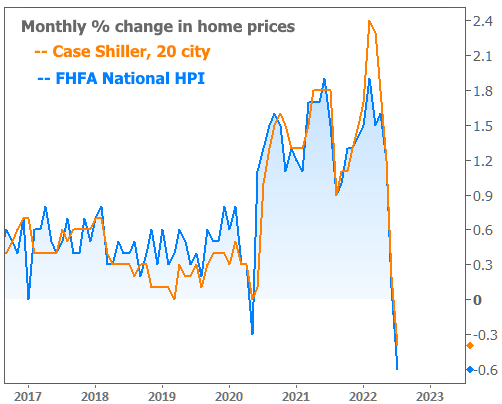

Whether or not changes have been “measured” is debatable. Certainly, if we use the apex of the recent housing and mortgage boom as a baseline, the reversal has been extremely abrupt. This is even the case for home prices, which normally lag farther behind rate hike cycles.

In new numbers for July released this week, both of the big home price indices recorded the biggest month-over-month declines since the great financial crisis.

But if we step back a bit and view the data in annual terms, it does indeed look more measured.

The catch is that the annual appreciation will certainly continue to drop in this rate environment. We can’t be sure how far it will decline. It’s certainly possible that it moves into negative territory, but if that happens, it’s important to understand that the powder keg of ingredients responsible for our current predicament is vastly different than 2008’s example. In other words, in 2008, the housing and mortgage markets CAUSED the downturn–a fact that both markets and consumers were slow to forget in the following years. In the present case, the housing and mortgage markets are in an infinitely better position to emerge strong from the economic downturn the Fed is determined to deliver.